This case study was written by Jan Lennartz, Data Scientist in Site Reliability Engineering at ING Belgium, and Kalyan Veeramachaneni Co-founder and CEO of DataCebo.

What are IT incidents, and why is it important to predict them?

At some point, you've probably received a notification that a web application is undergoing scheduled maintenance, and that service will be briefly disrupted. Many contemporary IT systems rely on microservices, with hundreds of such changes taking place on a near-daily basis. IT infrastructure teams plan these changes with the utmost care, making sure to communicate their timing and potential impact. Even so, these changes may cause disruptions, both foreseen and unforeseen.

A recent example where a small change caused a major disruption occurred on July 19th, 2024, when Microsoft computers around the world unexpectedly showed "Blue Screens of Death,” interrupting the work of major airlines, medical facilities, businesses and police forces. According to the cybersecurity company CrowdStrike, these outages were the result of a routine software update gone wrong. Insurers estimated that this one outage cost Fortune 500 companies around $5.4 billion dollars. Disruptions like these are costly and require significant (and high-pressure) effort to bring services back to acceptable levels.

Meanwhile, many enterprises use platforms like ServiceNow, Jira Service Management and others to centralize the complex management and deployment of IT infrastructure changes. Changes, incidents, disruptions, and root cause analyses are all logged in the platform, and incidents are linked to one or more changes. Anything from a small feature tweak to a major upgrade may cause an incident. IT teams at enterprises can use this data to develop a predictive model - would a change lead to an incident? This enables teams to be proactive rather than be reactive.

This is exactly what a team at ING decided to do. Leverage this vast data to build a machine learning model that can predict whether an incident (defined as Major, or P1, P2 events) may result from a planned change, and what type of incident it might be. With this prediction in hand, they can reduce risk by planning mitigations, implementing broader communication strategies, enforcing stricter change windows, delaying the change, or taking other proactive measures to significantly lower the likelihood of incidents. Out of the hundreds of changes occurring daily, the model highlights those with the highest risk of causing incidents, enabling teams with limited capacity to concentrate on the most critical cases

A lack of training data poses a major challenge in building these models—can synthetic data offer a solution?

To build this machine learning model, the ING team collected the historical data and did all the steps required to train a machine learning model (data labeling, feature engineering, model training, testing and validation). However, the team faced a model development challenge. The number of changes linked to incidents was significantly less than what is optimal for finding patterns between the two. A machine learning model trained on such imbalanced data tends to overfit to incident-related patterns, ultimately reducing overall accuracy.

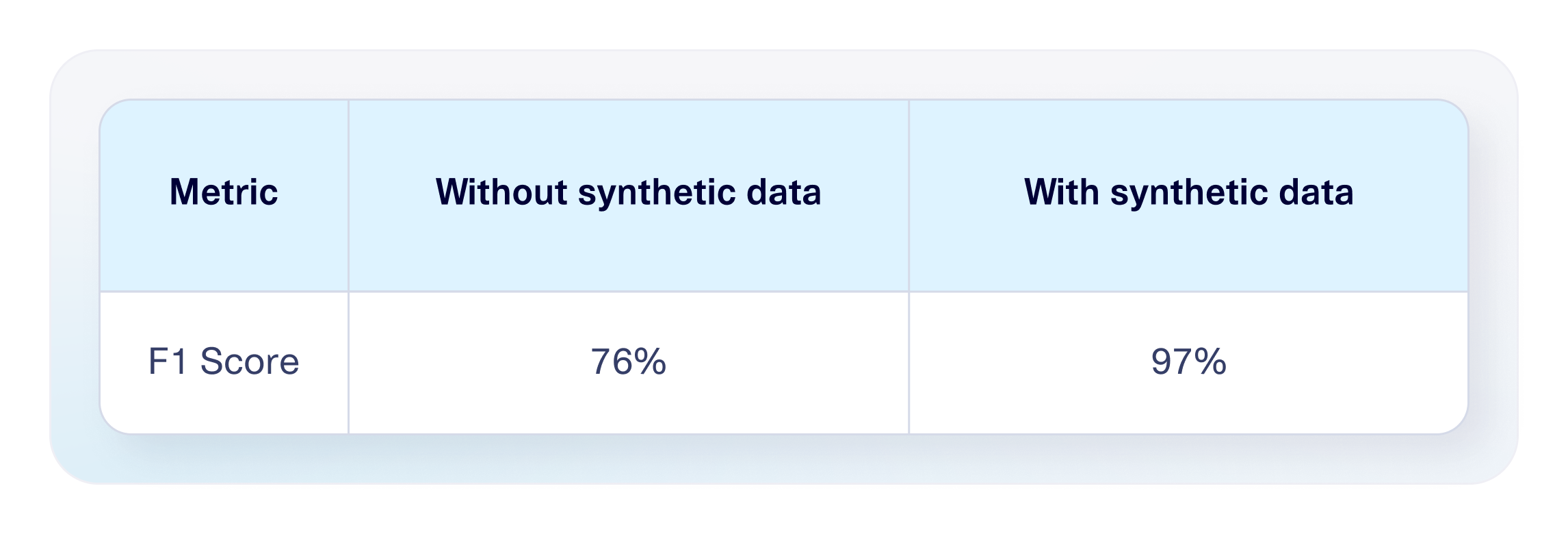

The team decided to explore whether synthetic data could help train a better model. Advances in generative modeling now allow organizations to train models on real data and produce synthetic datasets—a technique that is already helping many companies improve their fraud detection systems. With synthetic data they were able to increase the model accuracy by 21%. In this case study, we will briefly describe the process the team followed to add the synthetic data and how they tested and the result. We will follow up with a technical deep dive and best practices for incorporating synthetic training data.

Augmenting with synthetic data increased the prediction accuracy by 21%

Model training begins with historical, featurized, model-ready data—a dataset where each record represents a specific change, described by its features, along with a label indicating whether it led to an incident (1) or not (0).

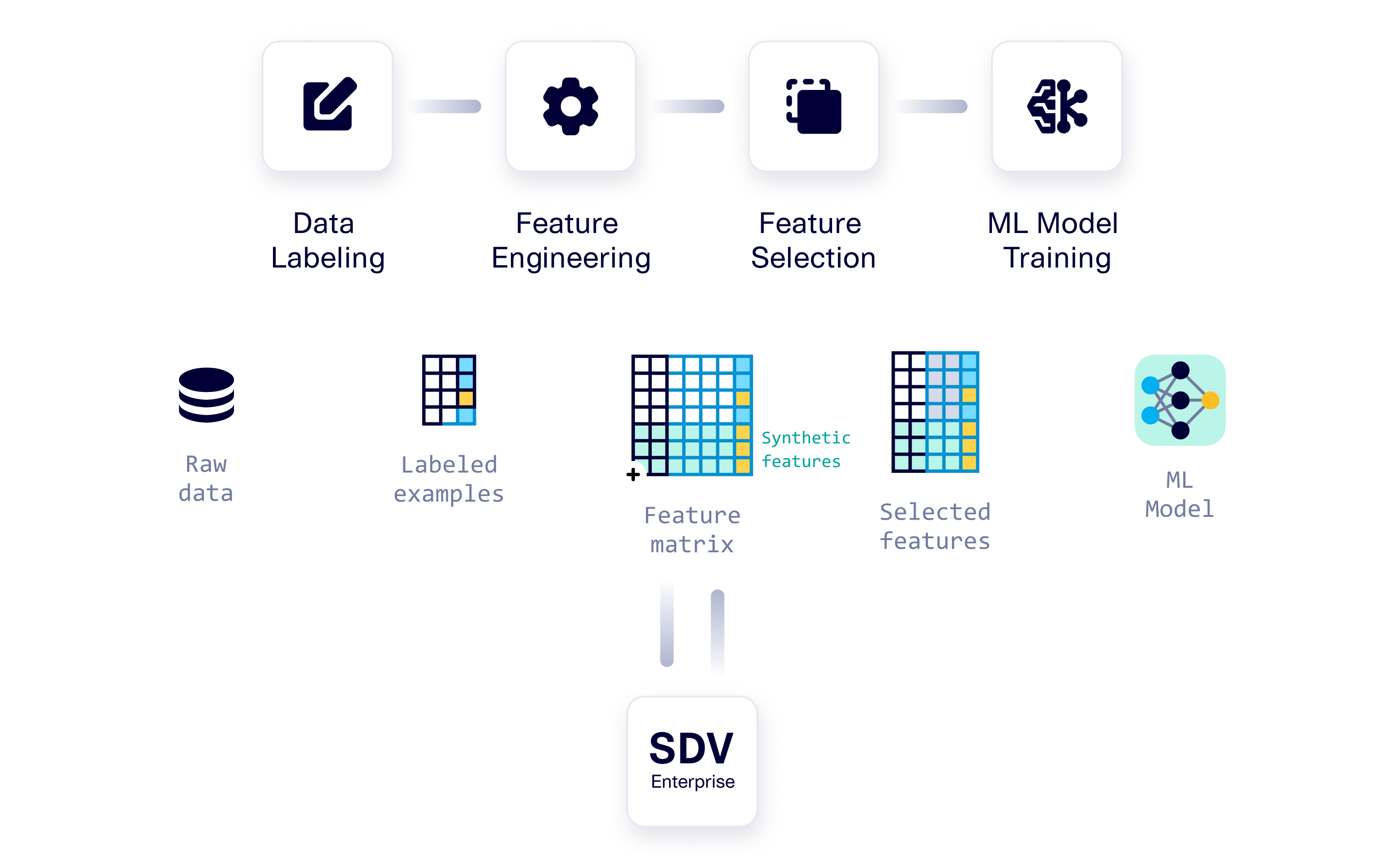

(Top) A classical workflow showing the steps to develop a machine learning model. (Bottom) Synthetic data is generated using SDV Enterprise to augment the training data.

In this context, synthetic data is produced by a generative model trained on the feature matrix derived from real data. The synthetic data replicates the statistical characteristics of the original dataset. Using the Synthetic Data Vault (SDV) Enterprise, the ING team built a generative model for their data.

Once the team created this generative model, they sampled synthetic data for the condition pertaining to either a Major, P1, or P2 incident. In this way, they created more data that was similar to the existing incident examples, but with slight variations. Training the incident prediction model on this additional data alongside the original data helps prevent overfitting, because such a model will fail on these new synthetic examples. It also provides additional examples for the model to learn from, helping it learn patterns.

Specifically, the process the team followed is:

Split the data into train and test. Training data is used to train both the generative model using SDV Enterprise and the prediction model using Lightgbm.

Use training data to train a generative model using SDV Enterprise. Because this model learns the structure and the patterns of the original dataset, it can generate realistic synthetic data.

Generate synthetic data using SDV Enterprise’s conditional sampling functionality to augment the training data. The synthetic data is specifically created for the less common category (changes that led to Major, P1 or P2 incidents).

Combine the real training data and the synthetic data, creating a balanced dataset to train the incident prediction model.

Perform feature selection to choose the most relevant attributes for predicting incidents, allowing the prediction model to focus on features that were most indicative of changes that were likely to lead to incidents.

Train the incident prediction model to predict whether a certain change will lead to an incident, using LightGBM.

Test the incident prediction model using the test data that was set aside at the beginning.

Result: The resulting incident prediction model achieved 97% F1 score up from 76%—a jump up of 21%.

This was the final result—but achieving it required answering several key questions, such as: How much synthetic data should be added? At what stage in the model development process should it be generated? And how can we test and ensure the model's robustness? In a technical deep dive that follows we will go through all these questions and recommend best practices for anyone trying to augment their training data with synthetic data.