Many organizations collect GPS data to get insight into customer behavior and to improve their operations. For instance, ridesharing and taxi operators collect GPS coordinates of vehicle positions, pickups, and dropoffs to improve future predictions of arrival times (see related articles from Uber and Lyft).

This can raise privacy and security issues. These GPS data points represent places where individuals live, work, learn, or socialize. It's possible to combine this GPS data with other data and identify the locations and movements of specific individuals, even if you don't have their names or addresses. This is often referred to as de-anonymization.

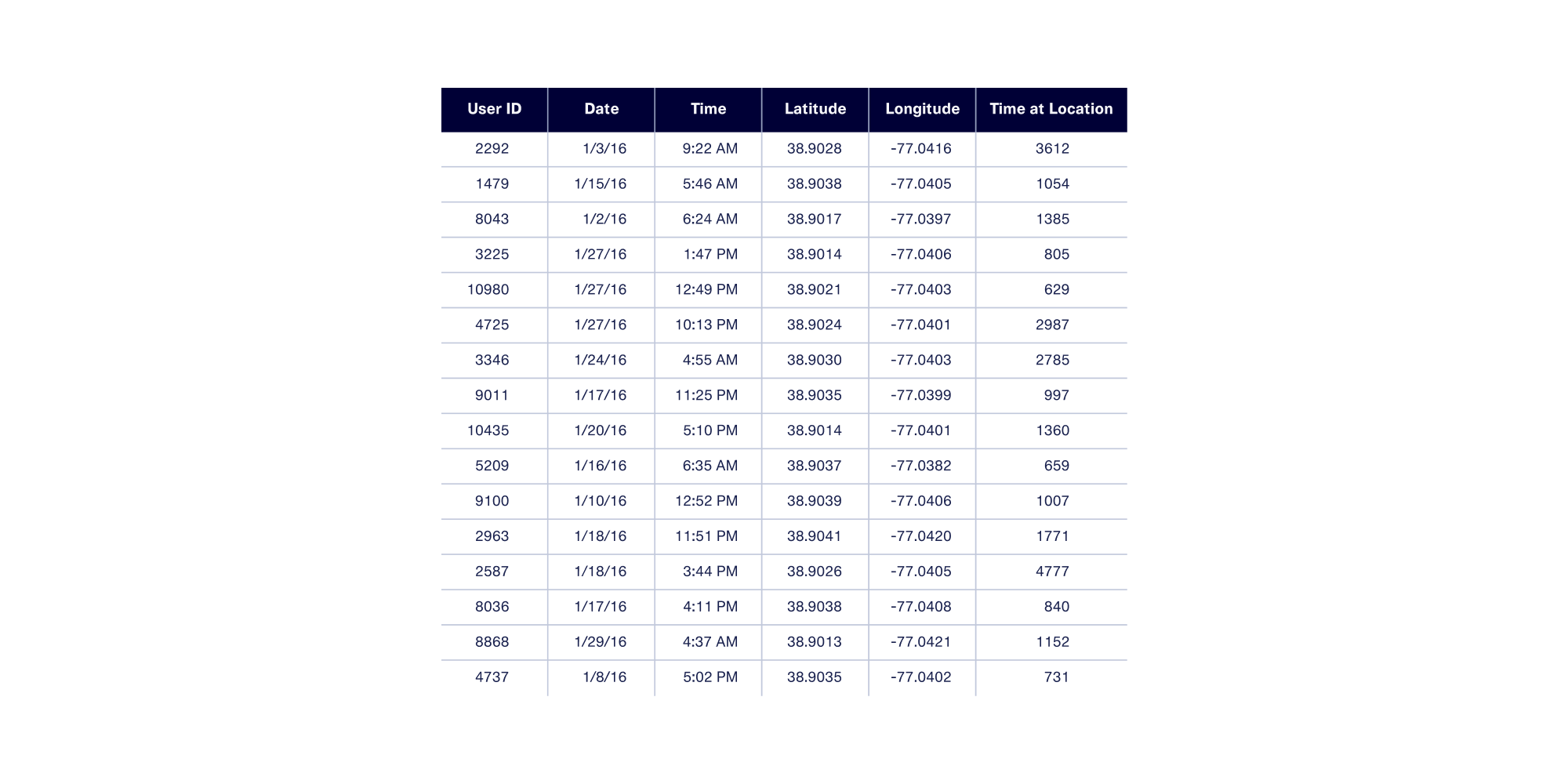

De-anonymization is powerful: In 2019, The New York Times used it to track a U.S. President’s whereabouts using a random sample of unlabelled cell phone pings. The dataset contained no directly identifying information such as names, addresses or phone numbers — only user id, dates, timestamps, latitude, longitude, and time at location values.

As this example shows, GPS data collected about an individual is generally considered personally identifiable information, or PII for short. While the precise definition of PII varies from country to country, most definitions agree that PII includes any information that can directly or indirectly identify an individual.

With that in mind, how can one share and work with GPS data without compromising privacy and security? A common solution is to apply anonymization techniques to the data. These techniques replace the original locations with alternative ones.

In this article, we’ll walk you through the challenges of working with GPS data and some techniques for anonymizing it.

Pure vs. Contextual Anonymization

It's possible to anonymize GPS data through pure anonymization — replacing real locations with others at random. While this technique preserves privacy, it generally eliminates correlations and other insights that make data analysis useful in the first place.

At DataCebo, we invented contextual anonymization as an alternative to pure anonymization. Contextual anonymization protects privacy while preserving the right amount of context based on the use case, so that data is still useful. In this blog post, we’ll build a shared understanding of how GPS data works, explore what makes anonymization difficult, showcase the features we’ve built to solve the problem, and finally showcase how you can layer these features with synthetic data using a real example.

What is GPS Data?

GPS coordinates are typically represented as a pair of values, called latitude and longitude, in one of 2 notation forms.

- Decimal Degrees (or DD): values are represented using floating point values

- Degrees, Minutes, and Seconds (or DMS): values are represented as text with degrees, minutes, seconds, and direction

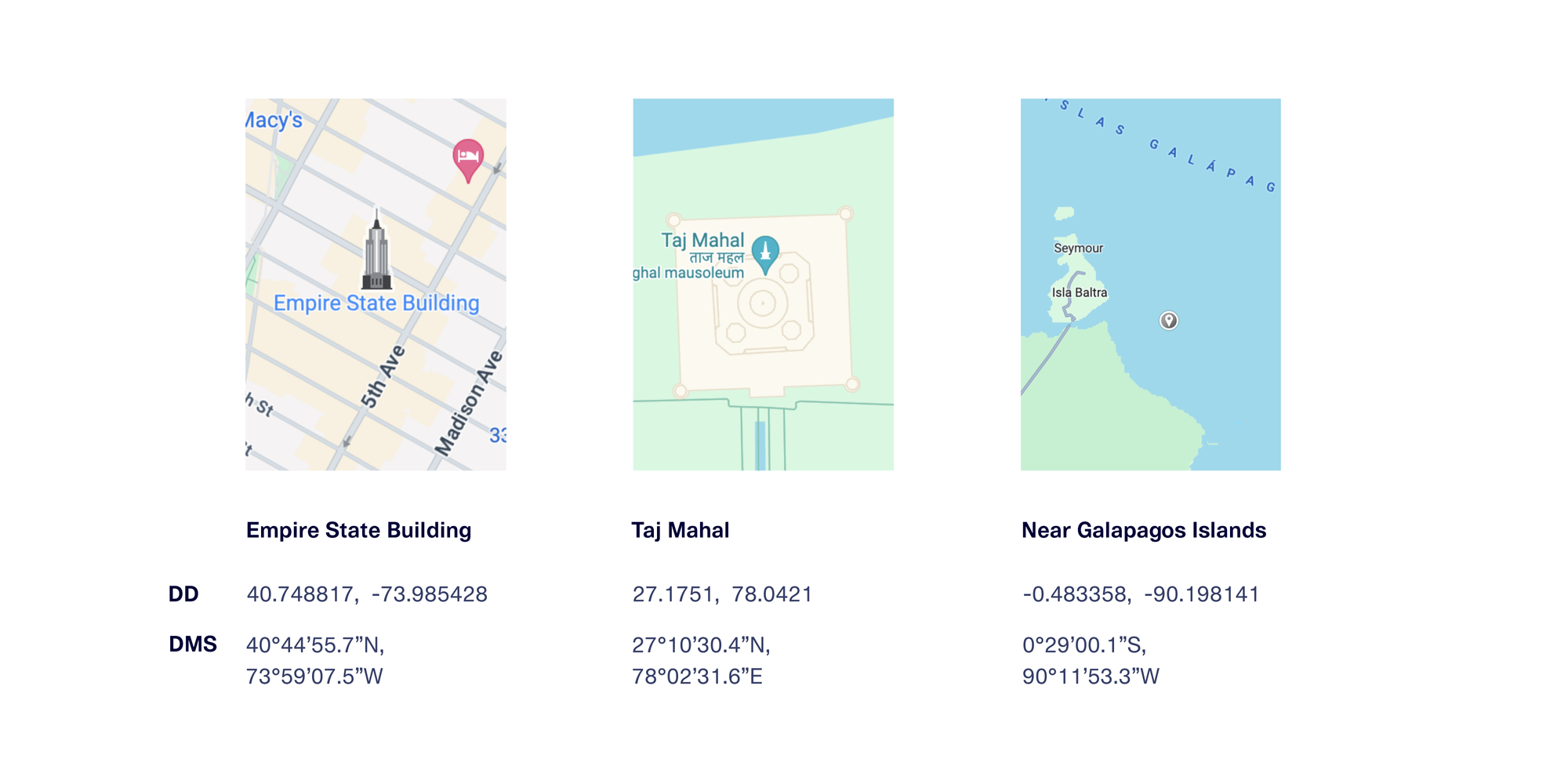

Here are some examples of GPS coordinates for a few famous places, shown in both formats.

Datasets and databases that store GPS data usually do so in decimal degrees notation, for a few key reasons:

- Floating point values can be stored with a higher degree of precision and more compactly than string values

- The format is easier to use in calculations and visualizations

- Many software tools natively work with or expect these values in DD notation.

For the rest of this post, we’ll use DD notation.

What do GPS coordinates actually represent?

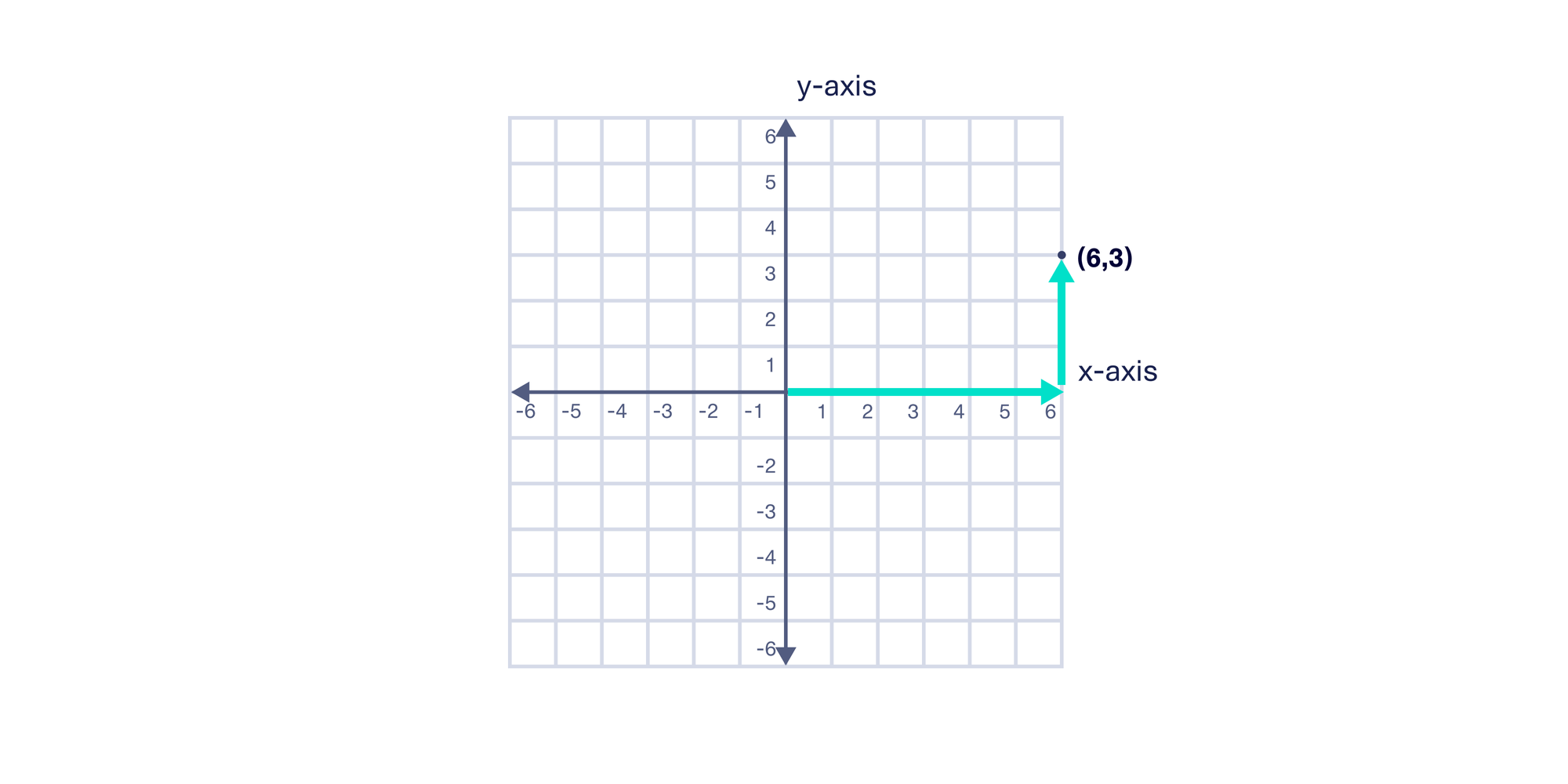

In a 2D Cartesian plane, the x and y coordinate values encode the horizontal and vertical distance from the center (0,0). The point (6, 3) describes the location 6 units to the right on the horizontal x-axis and 3 units up on the vertical y-axis. The x-axis and y-axis values combine to form a nice grid that spans the full 2D plane.

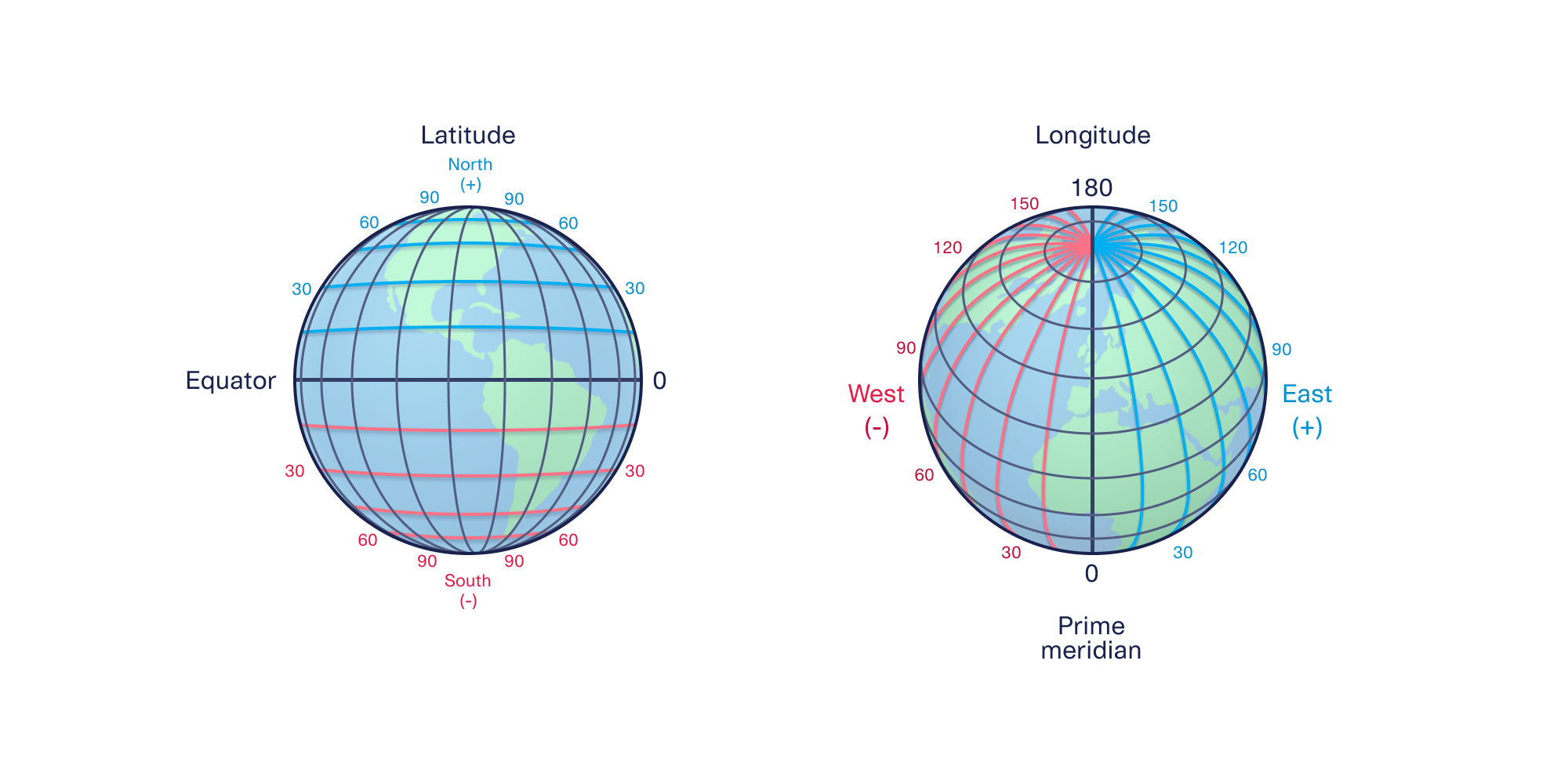

Because GPS coordinates are referencing precise locations on Earth, we need to extend this model to 3 dimensions. Instead of x and y coordinate pairs, we use latitude and longitude coordinate pairs.

Latitude values encode the angle North or South of the equator, while longitude values encode the angle East or West of the Prime Meridian. Latitude values range from -90° (the South Pole) to 90° (the North Pole), while longitude values range from -180° to 180°. We now have everything we need to draw a grid for Earth.

If we fix the latitude value and vary the longitude values across the full range, we can create a nice horizontal ring that wraps around Earth. If we instead fix the longitude value and vary the latitude values across the full range, we can create a nice vertical ring.

We can then repeat this for 10° increments to obtain the major latitude and longitude lines for Earth.

If we massively decrease the degree increments, we can reference any point on Earth with varying degrees of precision:

- 0.1° increments provide ~10 kilometer precision

- 0.01° increments provide ~1 kilometer precision

- 0.001° increments provide ~100 meter precision

- 0.0001° increments provide ~10 meter precision

- 0.00001° increments provide ~1 meter precision

Because of Earth’s shape, precision will be higher at the same granularity near the poles and lower near the equator.

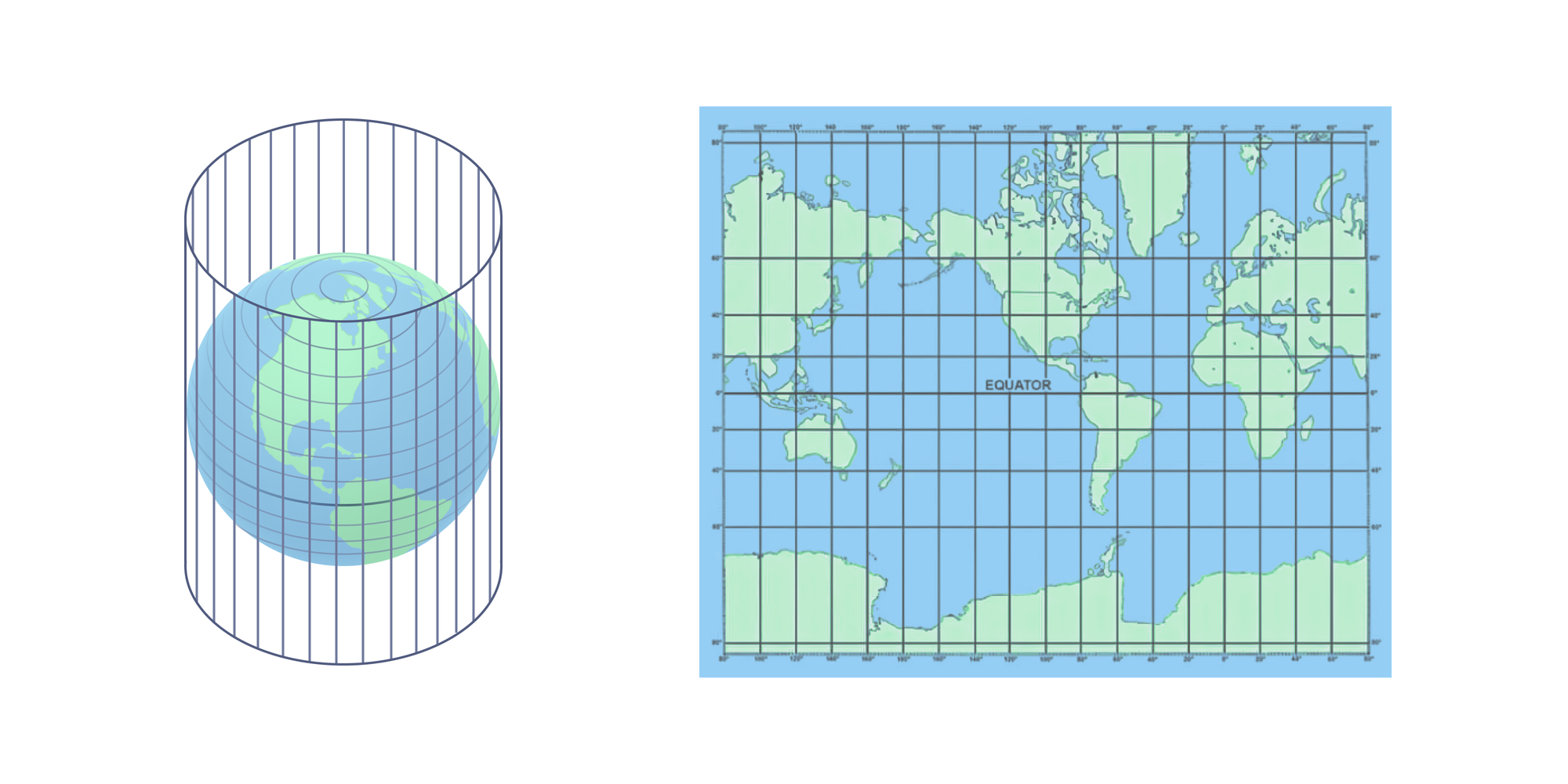

To convert 3D points on Earth to a 2D map, cartographers over time have invented different map projections. Map projections are mathematical transformations that convert points on a 3D surface (like an ellipsoid) to a 2D plane by making certain tradeoffs.

The Mercator projection is one of the most popular map projections. It's used in most mapping software applications (Google Maps, Apple Maps, Waze, etc) as well as for many navigation-oriented physical maps (like marine navigation).

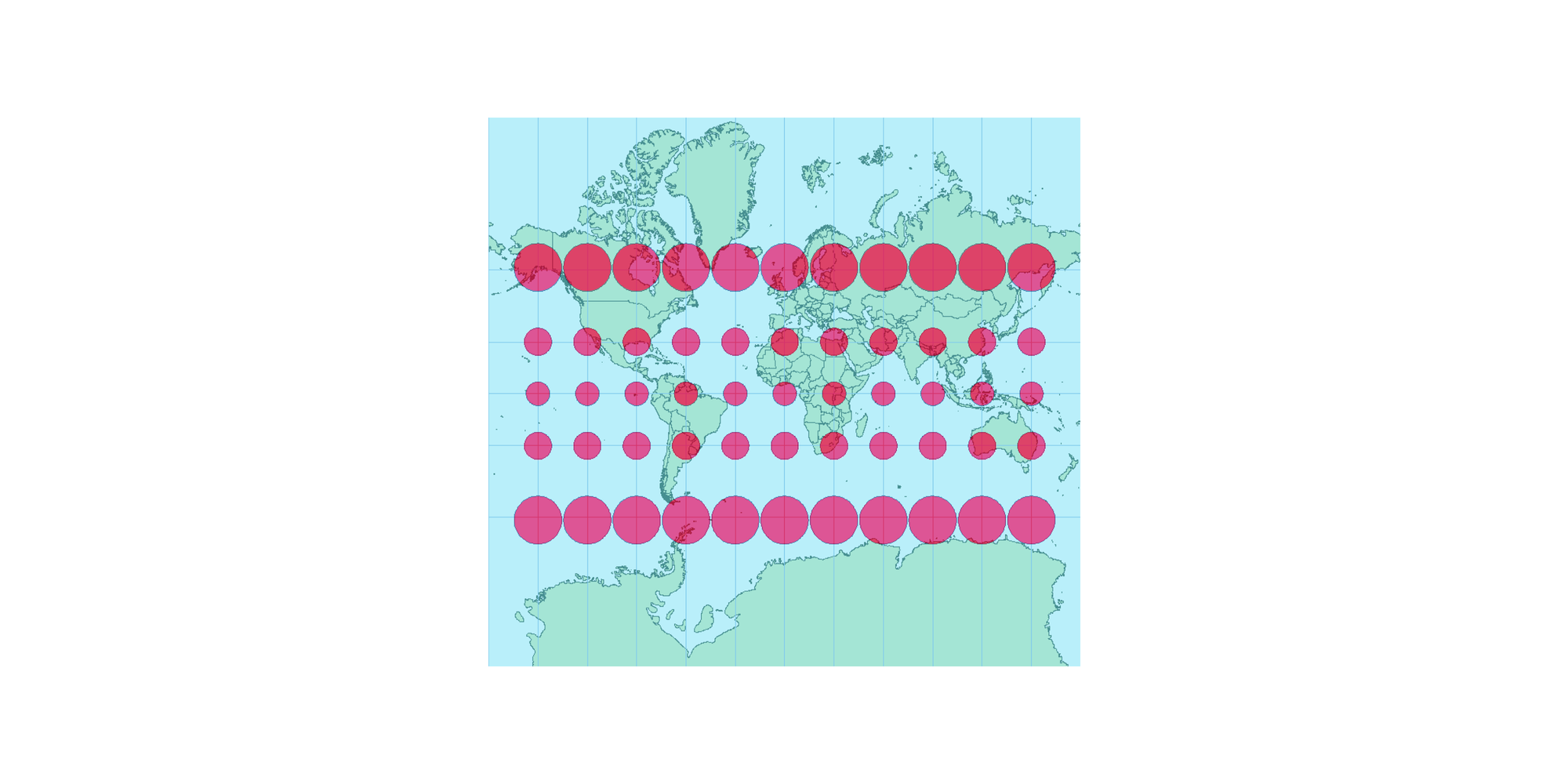

This projection does a good job of preserving angles and shapes in localized areas, which makes it useful for navigation. The tradeoff is that areas near the poles are distorted and appear much larger than they actually are. The diagram below shows the extent of this distortion using circles — if you imagine that the circles represent areas of the same size, you can see how the projection stretches or condenses them depending on their distance from the equator.

In this section, we went deep into how GPS data works and what it represents — but we’ve only scratched the surface! As you might expect, the complexity of GPS data makes it quite challenging to anonymize.

Anonymizing coordinates by simply adding numerical noise to latitude and longitude values independently doesn’t work because of the underlying shape of Earth. GPS coordinates are expressed in degrees, but as humans we think in terms of geographic boundaries (like postal codes, states, or countries) and distance units (like kilometers). Creating simple interfaces for data controllers that hide the complexity of GPS data but still preserve the right amount of control also presents its own challenges.

To tackle this challenge, DataCebo got creative. In the next few sections, we’ll walk through the contextual anonymization features we created specifically for GPS data.

Contextual Anonymization for GPS

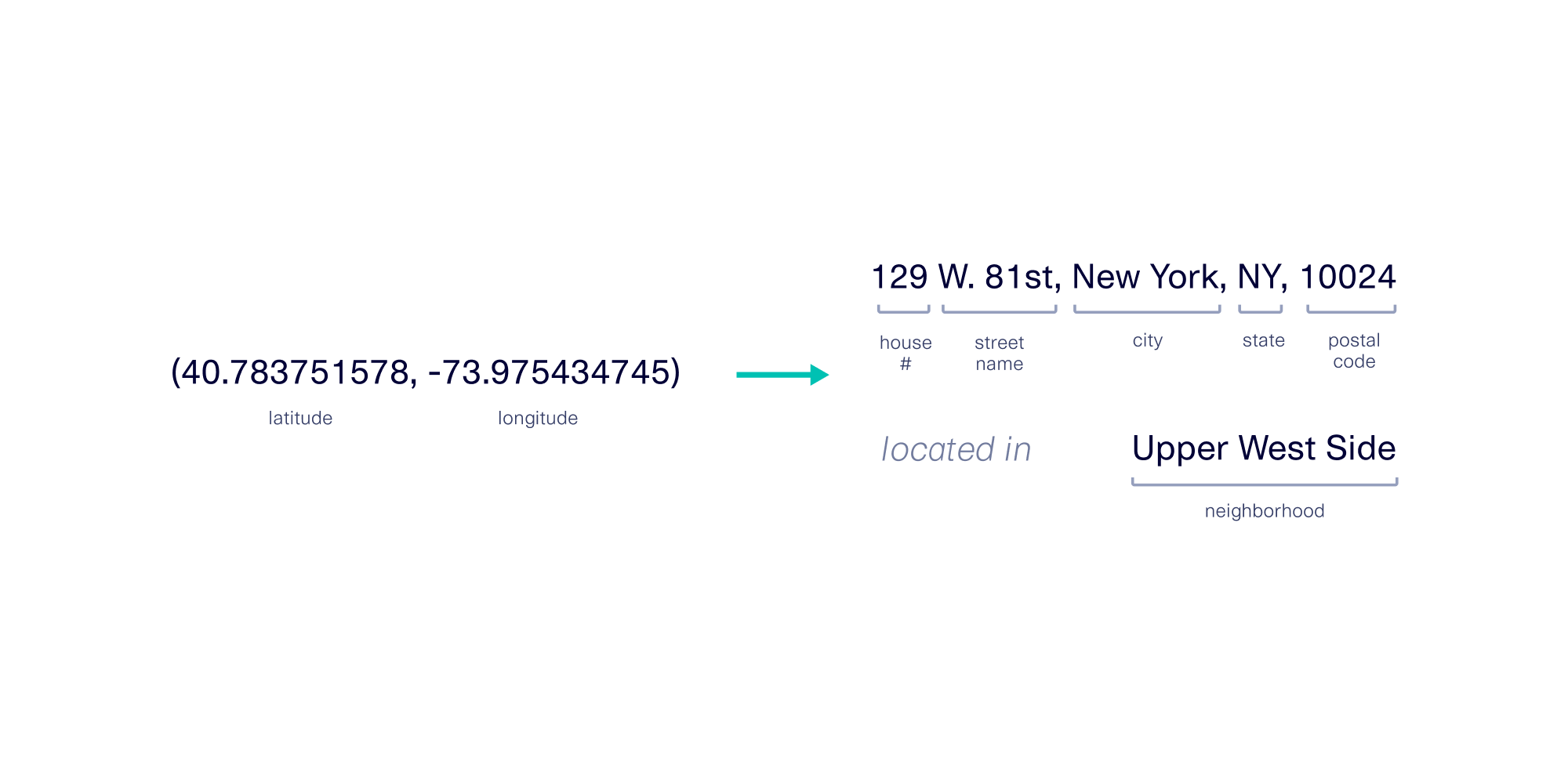

GPS coordinates can reflect a lot of contextual information, which can be derived using additional databases. For example, using a reverse geocoding tool, GPS coordinates can be converted back to physical addresses.

Because GPS data can encode for many different types of information, anonymization tools should empower data controllers to define the context they want preserved for downstream applications. In addition, the risks of re-identification can vary based on the combination of the technique used and the population density of the region(s) it’s applied to.

With this in mind, we’ve created two different contextual anonymization features for GPS data:

- GPS Noiser: For noising globally using your choice of distance Noising Globally Using Distances

- Metro Area Anonymizer: For anonymizing within metro areas

GPS Noiser: Noising Globally Using Distances

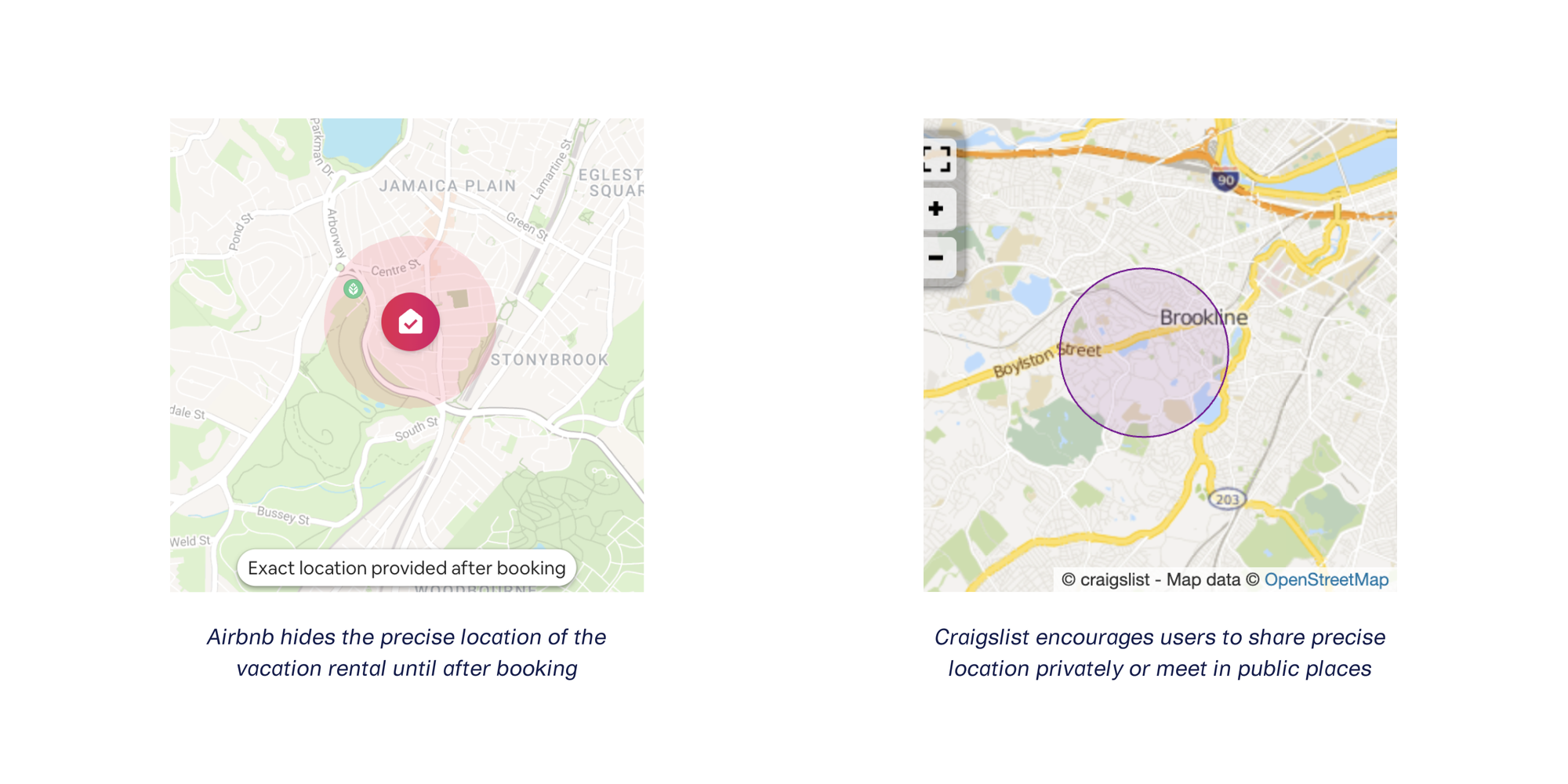

Obfuscating specific locations by adding distance-based noise is a common way to preserve user privacy. Many websites and applications use this approach, in which a pinpoint-precise location is replaced with a nearby zone of locations.

For those who want to use a similar strategy, we created the GPS Noiser transformer.

Because downstream users of this data expect GPS coordinate pairs instead of a zone of potential locations, we designed this transformer to replace the original GPS coordinates with nearby ones.

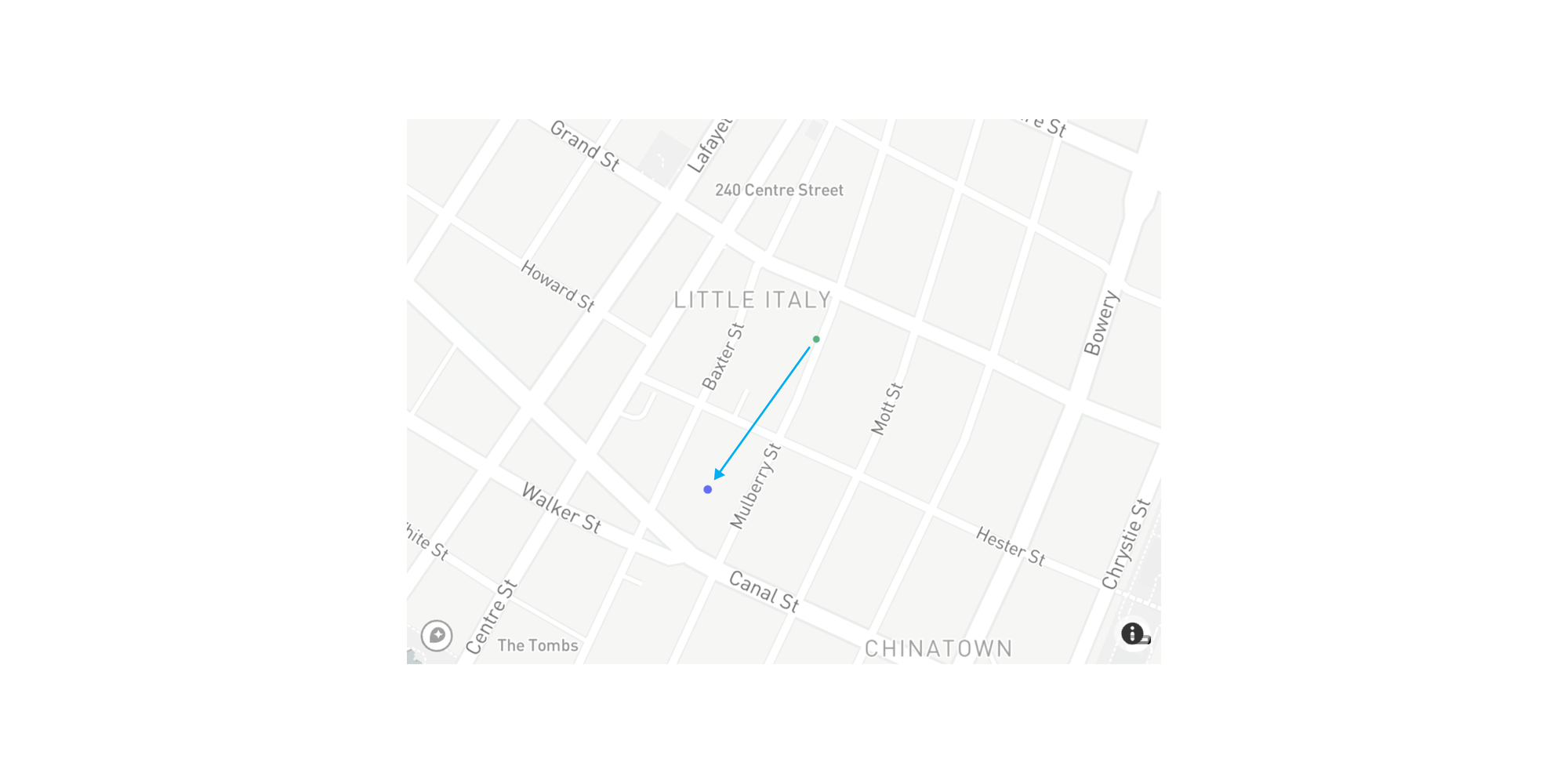

Here’s a before and after example of GPS Noiser in action for a single point in New York City.

Because New York City is so densely populated, a zone of 0.2 kilometers is sufficient to anonymize the specific house or apartment building that an individual might reside in.

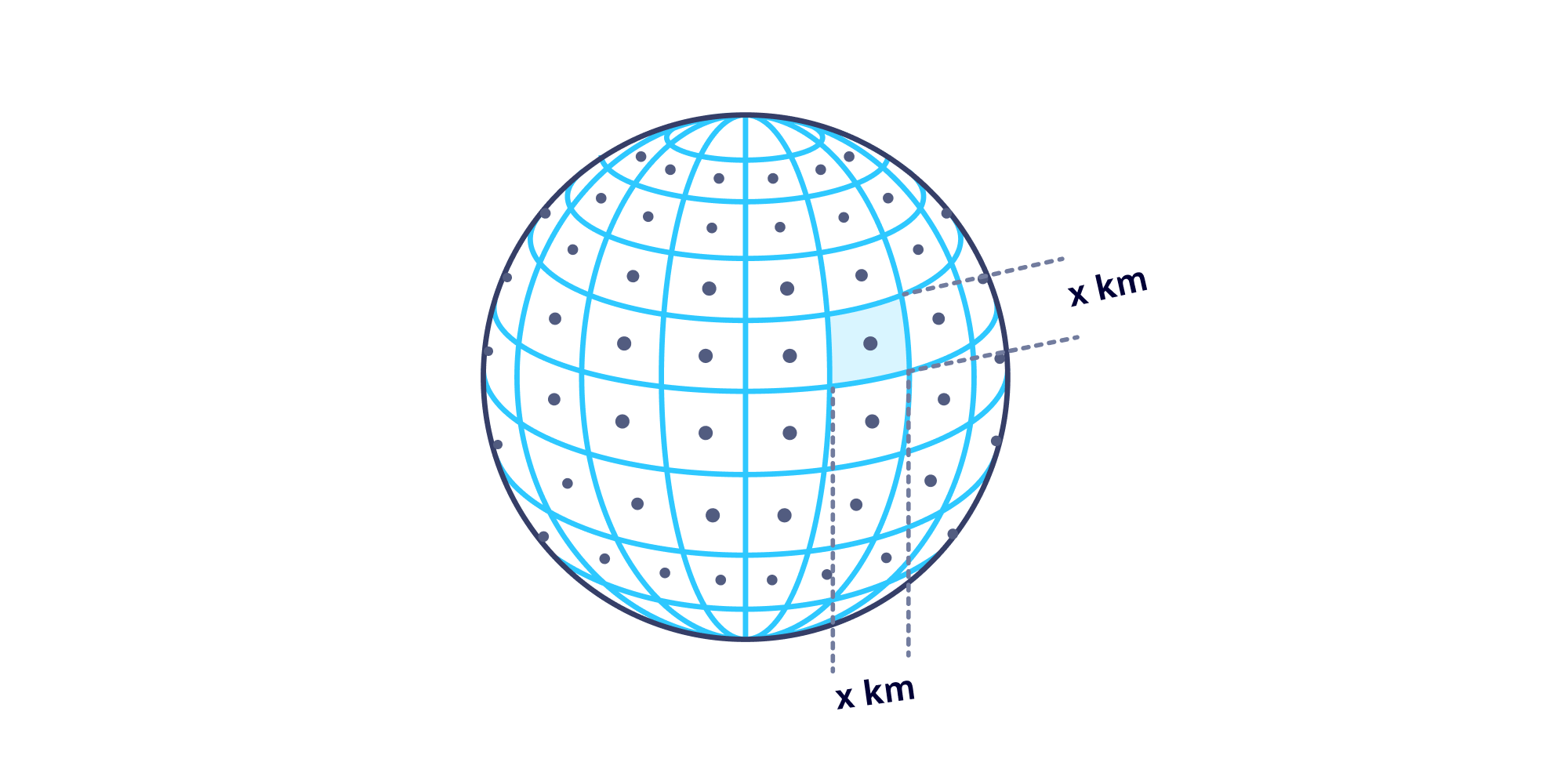

Here’s a breakdown of how this works from a technical standpoint. Internally, the GPS Noiser transformer:

- carefully generates a grid over Earth where the edges are ~0.2 kilometers long

- identifies which grid our single point falls into (as well as the corresponding GPS coordinate boundaries)

- chooses a random point inside that grid and returns that value

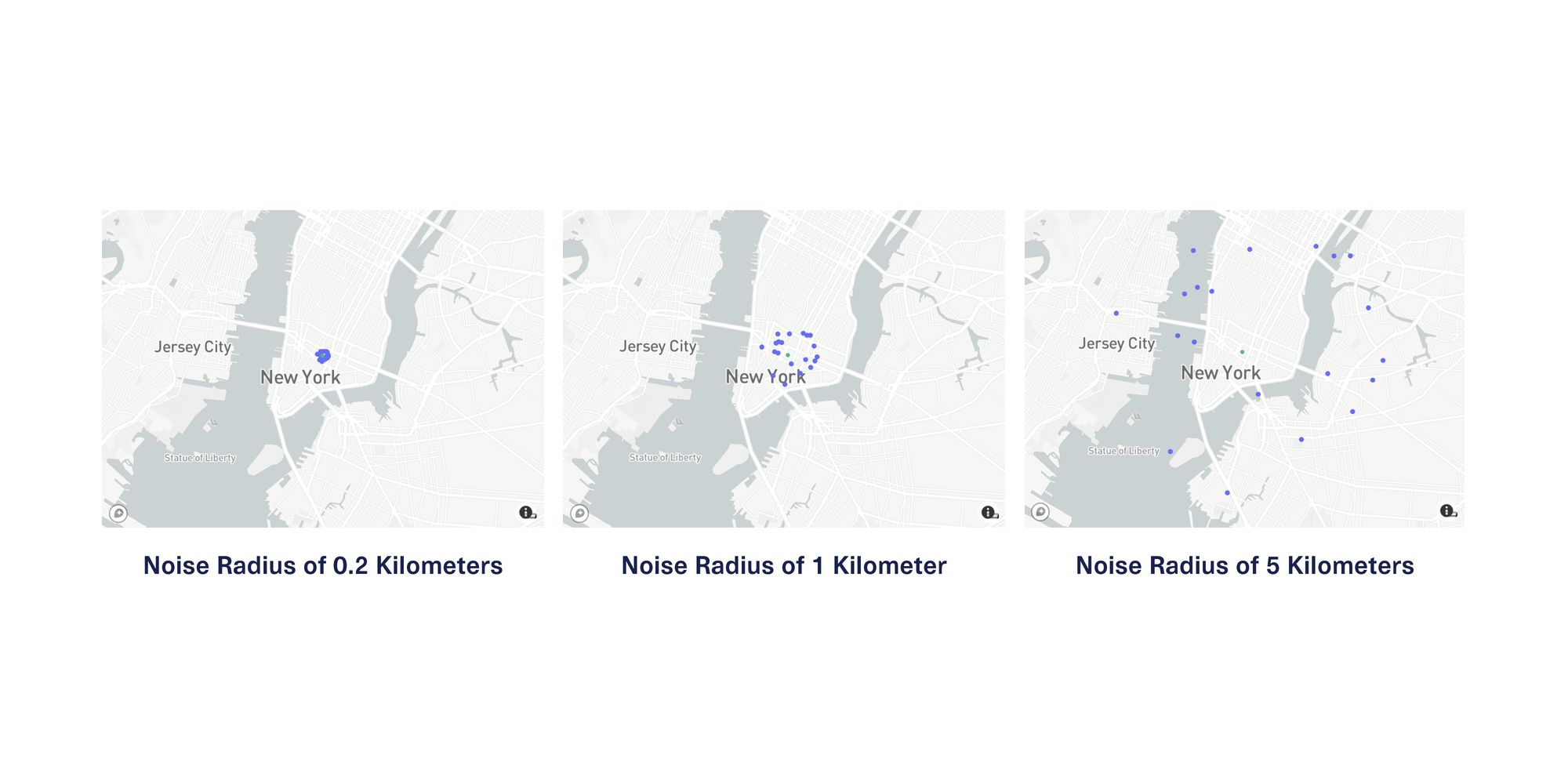

Because regions vary wildly in population density, you can customize the radius of the zone used for the replacement GPS coordinate values. The following diagram provides a side-by-side comparison of 20 values anonymized from the same starting GPS coordinates using different radius values.

In a dense area like New York City, a downstream user of this data will likely find the data with 0.2 kilometers of noise the most useful of these 3 choices because it approximately preserves the context of the city blocks and neighborhoods that the locations reside in.

However, in more sparsely populated areas, you may need to use a larger noise radius to reduce the risk of re-identification. For instance, in suburban Texas, homes can span multiple acres, and in rural Iowa, farms and estates often span multiple square kilometers.

Metro Area Anonymizer: Anonymize Within Metro Areas

What if your GPS data spans a large number of regions that range drastically in population density? In that case, using the GPS Noiser would involve using different noise radius values each time and carefully verifying that anonymity is preserved.

A better approach for this situation anonymizes locations within the context of human density, which changes throughout the world. Luckily, we have a helpful proxy for this — postal codes. The geographic boundaries of postal codes indicate how densely populated different areas are:

- High-density postal code regions tend to have a smaller geographic footprint

- Low-density postal code regions tend to have a larger geographic footprint

We created the Metro Area Anonymizer transformer to automatically detect the postal code that corresponds to each GPS coordinate pair, and replace it with another random pair of GPS coordinates inside the same postal code boundary. Here’s a before and after example of the Metro Area Anonymizer in action for the same original GPS coordinates in the last section’s example.

The additional benefit of this approach is that any derived postal code-level statistics and analyses will still be valid without exposing any of the original, precise locations. The following diagram shows contextual anonymization using the Metro Area Anonymizer for 1000 GPS coordinates in the greater NYC area.

Takeaways

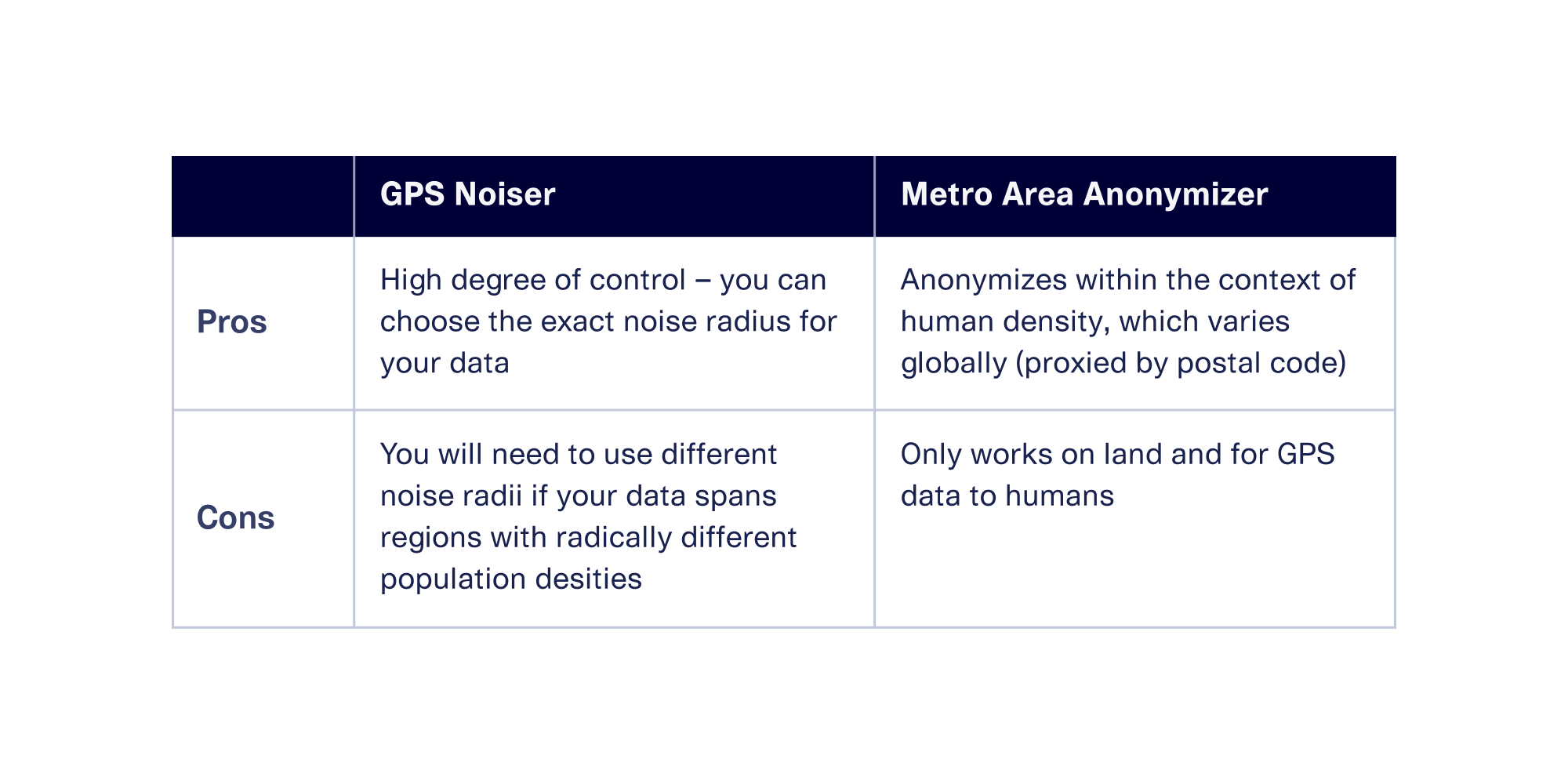

Which is the best tool for your situation? Both of these approaches have pros and cons, as shown in the table below:

Contextual Anonymization Improves Synthetic Data Generation

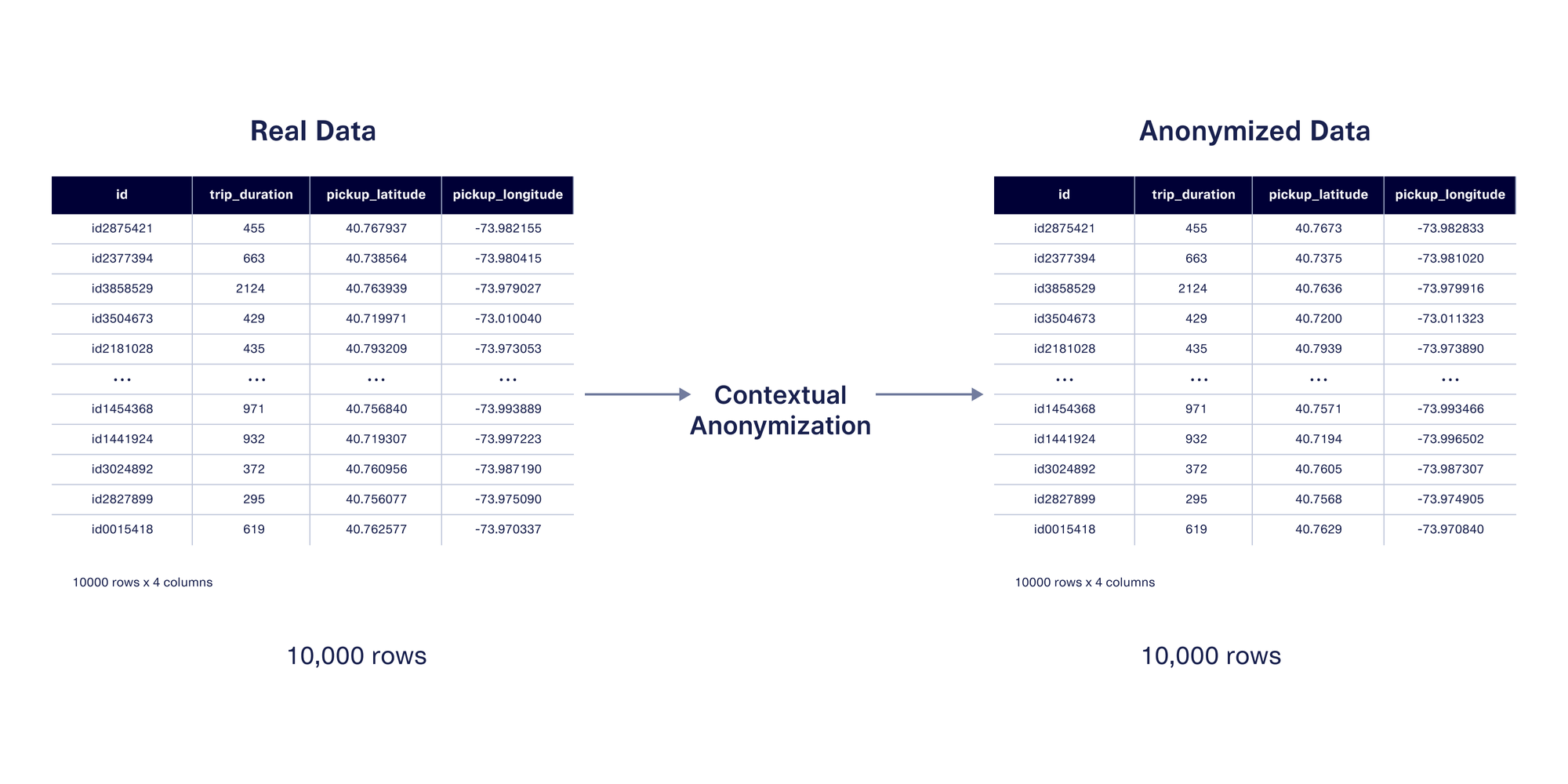

These two contextual anonymization techniques are incredibly useful when you want to anonymize GPS data in a direct, 1:1 fashion.

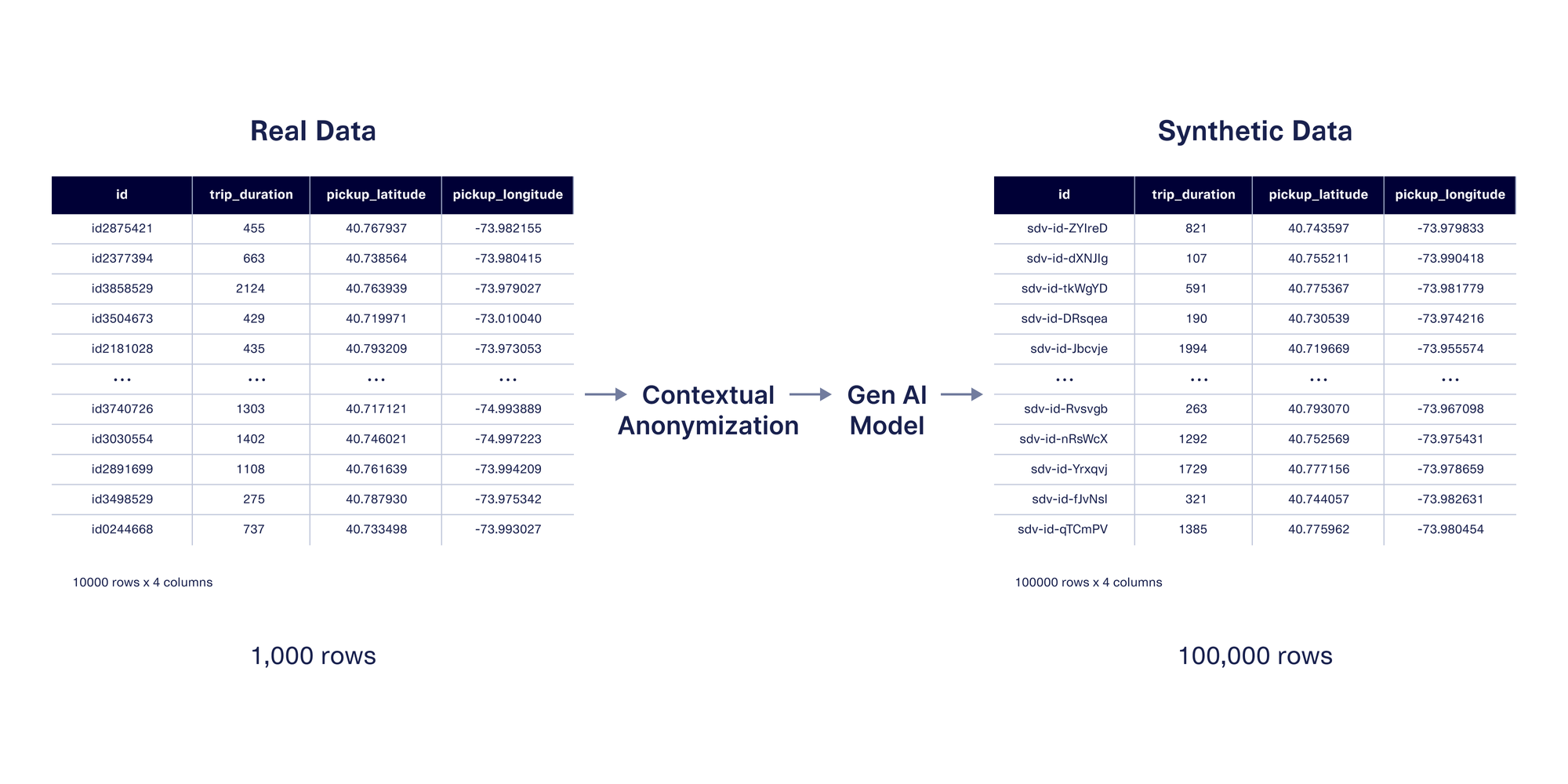

These techniques can also be used when generating synthetic data, which mimics the same format and patterns as the original data. The benefit of synthetic data is that you can create more data than you had originally, rather than only anonymizing existing values. If you're using SDV Enterprise, the features we showcased in this post will allow you to control how close the synthetic GPS values are to the original ones.

Next Steps

In this post, we explored the two contextual anonymization approaches we created specifically for GPS data. We’re excited to empower more organizations to safely leverage the first party GPS data they’re collecting, or to exchange GPS data more comfortably with third party providers.

Contextual anonymization is available to licensed users of the SDV Enterprise edition. However, anyone can test our basic anonymization techniques for proof-of-concept. Head over to the SDV docs to explore today!